A collaborative project developed by artist Guy Fredericks, Studio A, Dr Chloe Watfern, and MAG&M, Bleeding Hearts and Morning Glory is a socially engaged exhibition that encourages people with intellectual disability to participate in conversations about climate change and care for place.

Here is the catalogue essay I wrote:

Tending the World

Guy Fredericks has been tending the world through his art for many years now. He has been quietly, carefully, reverently making delicate drawings, paintings and sculptures of all kinds of creatures, from blue-ringed octopi to beagles. He once worked in a plant nursery, and has a Certificate III in Parks and Gardens, and a Certificate II in General Horticulture. Now, working at Studio A, he is the resident recycler, reclaiming any salvageable waste from the rubbish bin, and making sure each category of recyclable finds its way to the right place.

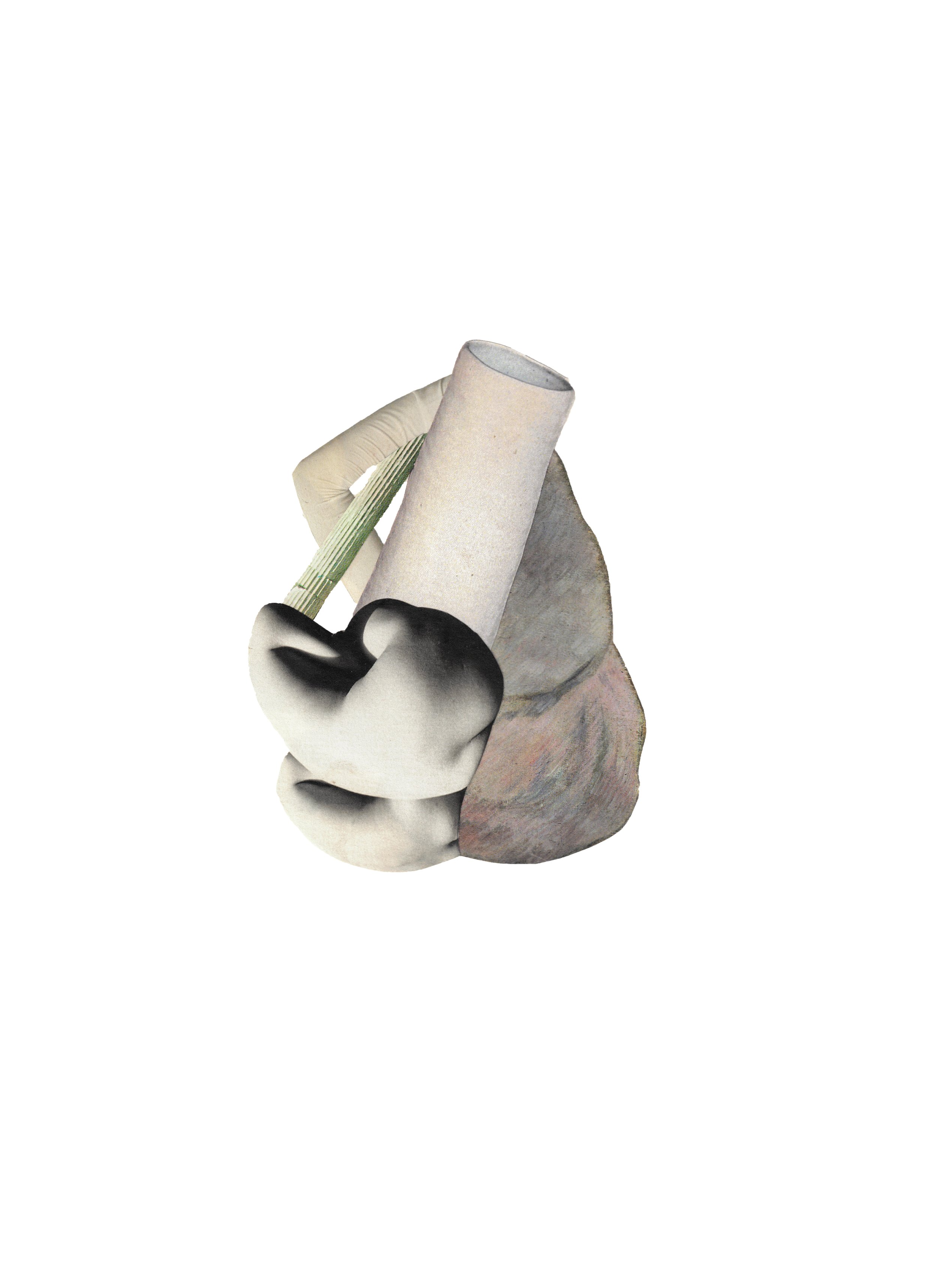

More and more, Guy’s creative work has taken on an element of advocacy: he wants to raise awareness about what’s happening to the environment. For example, his 2022 sculpture Earthenseed was a response to the climate emergency. The sculpture is, in Guy’s words “a planetary atmospheric seed that harbours life… The tree is struggling…but it’s not beyond saving and just needs a bit of help from mankind.”

“It’s like you’re looking down at the world from above”, said Ben, one of a team of neurodivergent environmental workers from Bushlink, who joined us for an art workshop in late August 2023. He was looking hard at a picture of Guy’s artwork, then back up to Guy, then down again at the printout. We had already met this man, wearing the same uniform of high-vis orange fleece, on a previous visit to a site less than a kilometre away - a slim corridor of bushland between main roads between Gayamaygal and Garigal Country in Curl Curl, on the Northern Beaches of Sydney. Then, he had shown us how their team tend to the wild (and not-so-wild) places in our midst, like the bank where we stood beside a small bridge connecting an oval to a bowling club, spotted with Banksia, Acacia and Lomandra.

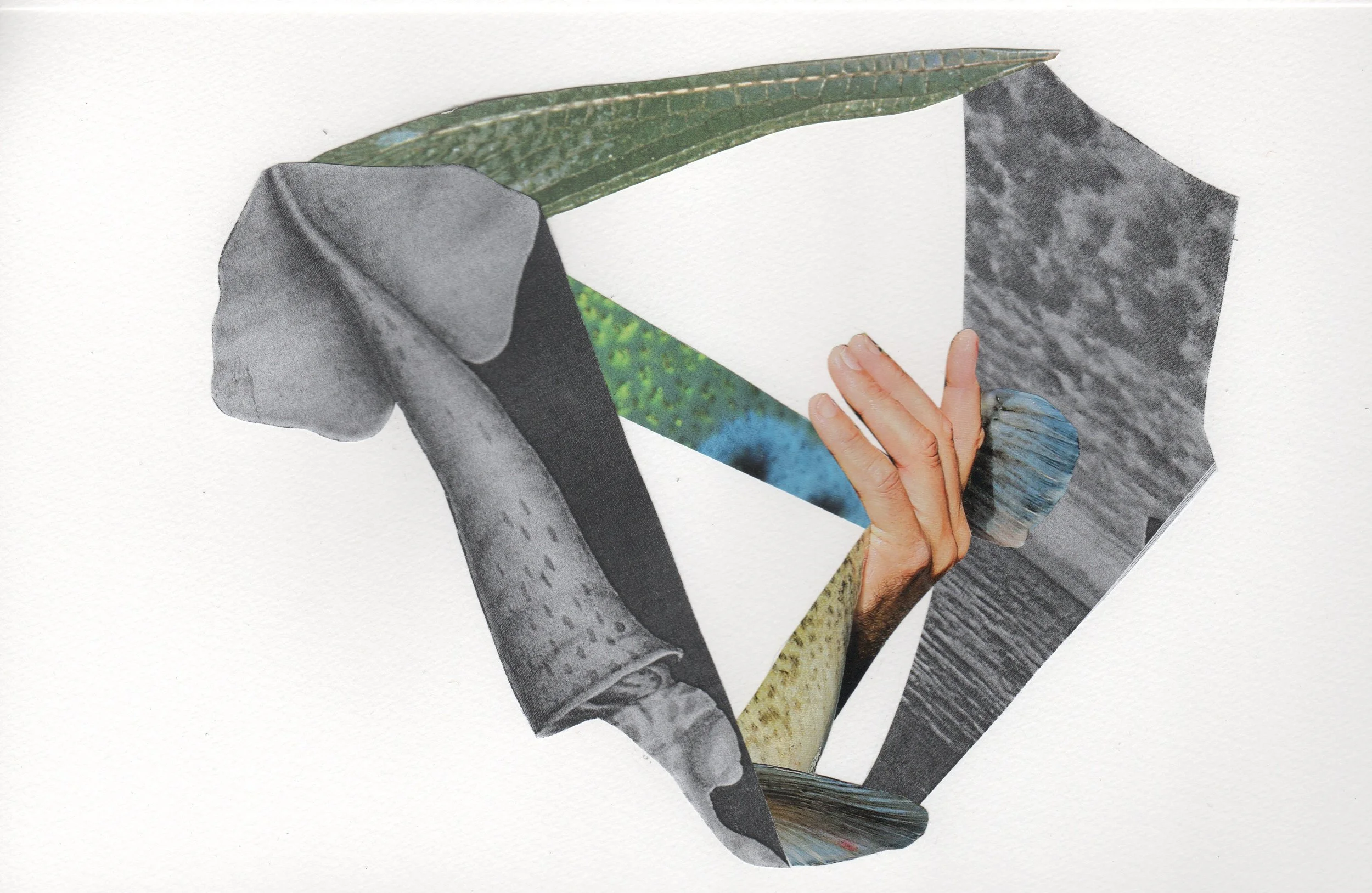

They had spent that morning pulling out the Morning Glory, that ubiquitous but destructive weed with beautiful purple flowers. If you let it go it strangles the trees, cutting out sunlight to the middle stories and undergrowth. The Bushlink team pull the vines up from their roots, which criss-cross the ground, and not from the leafy parts that twist around the other plants. Then, they wind the vines up like lassoes and hang them from branches or push them into the mesh wire of a border fence, where they dry out and can’t regrow. As we went walking together towards the main road, past the lagoon, we noticed dozens of lassoes hanging all along the track: a sign of the care these workers have taken of this small parcel of bush over the years. We collected a few, which Guy took back with him to the studio. They seemed to us like ready-made sculptures. For me, their tangled but looping forms evoked something hard to articulate about the mess of this climate era, and how we might each respond.

“What do you think about climate change, Guy?” Ben from Bushlink asked as we gently edged into our workshop that August morning. “Do you think we should take action? Guy, what’s climate change?”

Guy gently ignored the first part of the question and focused on the second. Perhaps it’s an easier one to answer. “People have observed the weather over a long period of time,” he explained. “They’ve noticed significant changes in the amount of carbon in the atmosphere compared to pre-industrial levels...” Guy continued to deliver a highly accurate and convincing analysis of the effects of climatic changes on various elements of contemporary life, and then he moved adeptly into the task at hand – to pay homage to the lassoes that we had gathered on the table before us, some already worked into and woven by Guy and Emma Johnston, his long-time supporter at Studio A, others picked straight from the Bushlink regeneration site.

The seed of this project was the fact that people with intellectual disability – like Guy Fredericks, like the team at Bushlink – are rarely included in conversations about climate change. I’ve dug into this in the research literature. Everything published about climate change and people with intellectual disability (spoiler alert, there are 13 academic articles in total), focus on increased risks during the natural disasters that are induced and exacerbated by global warming. In other words, people with intellectual disability face higher rates of injury, more long-term effects on mental health and wellbeing, and less inclusion in preparation efforts.

However, little has been said, made, written, sung – you name it – that helps balance this narrative. What about the stories of love, imagination, and care? And how might people with intellectual disability lead conversations about a topic like climate change? It is something that is notoriously hard to talk about; so abstract and global and diffuse. We had a hunch that the answer might lie in this tree, or that plant; an atmospheric seed; a morning glory lasso. We all need something concrete to bring us back to earth.

And so, in our small group around some trestle tables on the last day of winter, we continued to talk as we started to draw and weave and fiddle with the lassoes laid out on the table before us. The Bushlink team told us about encounters with birds and dogs while on the job. They told us more about what they do: lopping and pulling, pruning, and trowelling; giving plants space to grow. “The worst part of it,” said one man, “is not coming back to that specific site. I feel like I’m making it an art form, but I’m not going to see it again.”

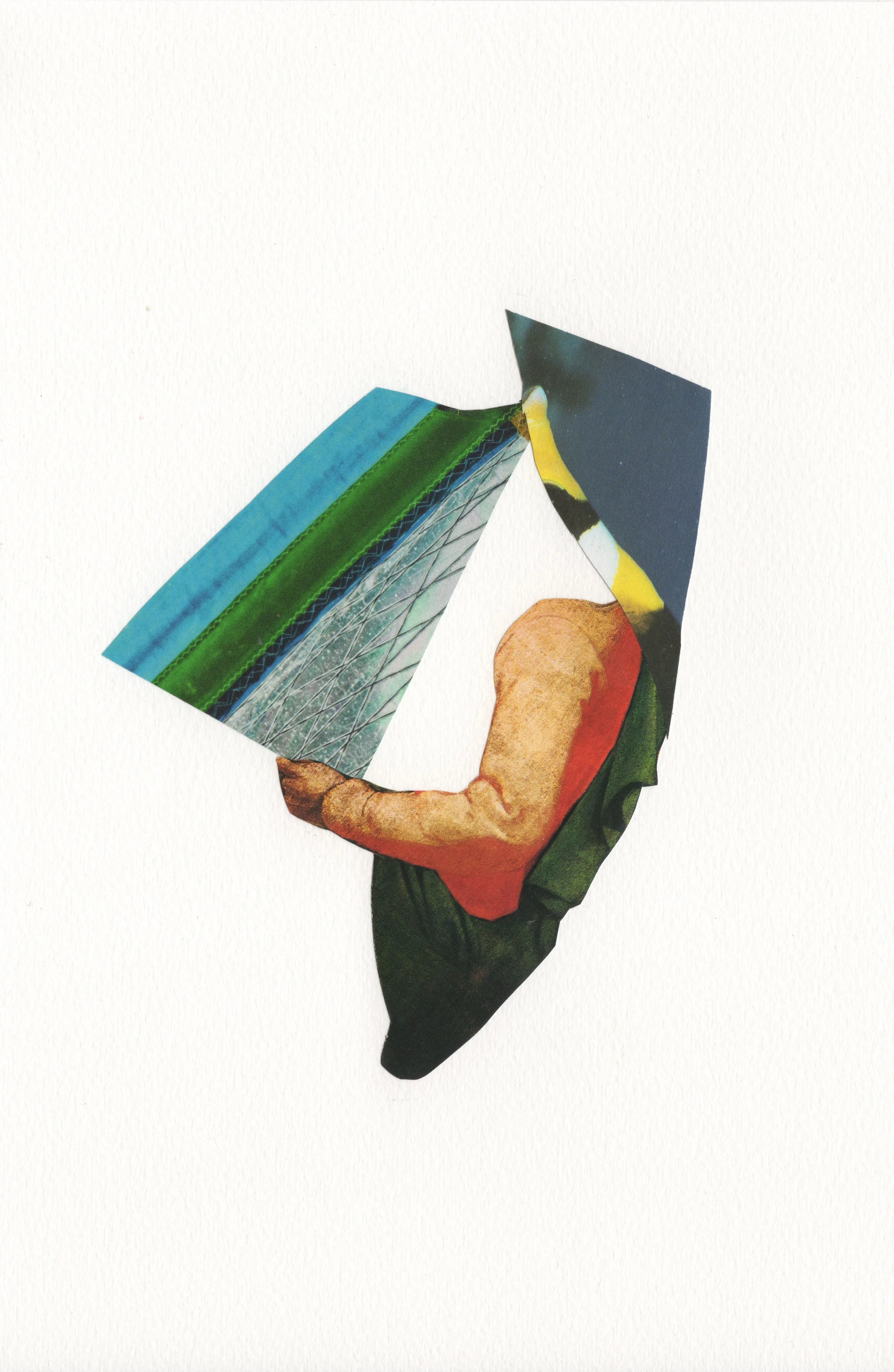

By the end of our few hours together, all kinds of things had emerged. Ben started drawing a lasso, but then it became a nest, and then a tree in the sky on a windy day, the leaves flying everywhere, and a mother bird protecting her babies. Tarek traced the shadows cast by the Morning Glory on a white sheet of paper: like a flower or the sun, like waves on water. Dylan noticed that the curves of the vine looked like flames, so he started adding detail. It was a lasso on fire.

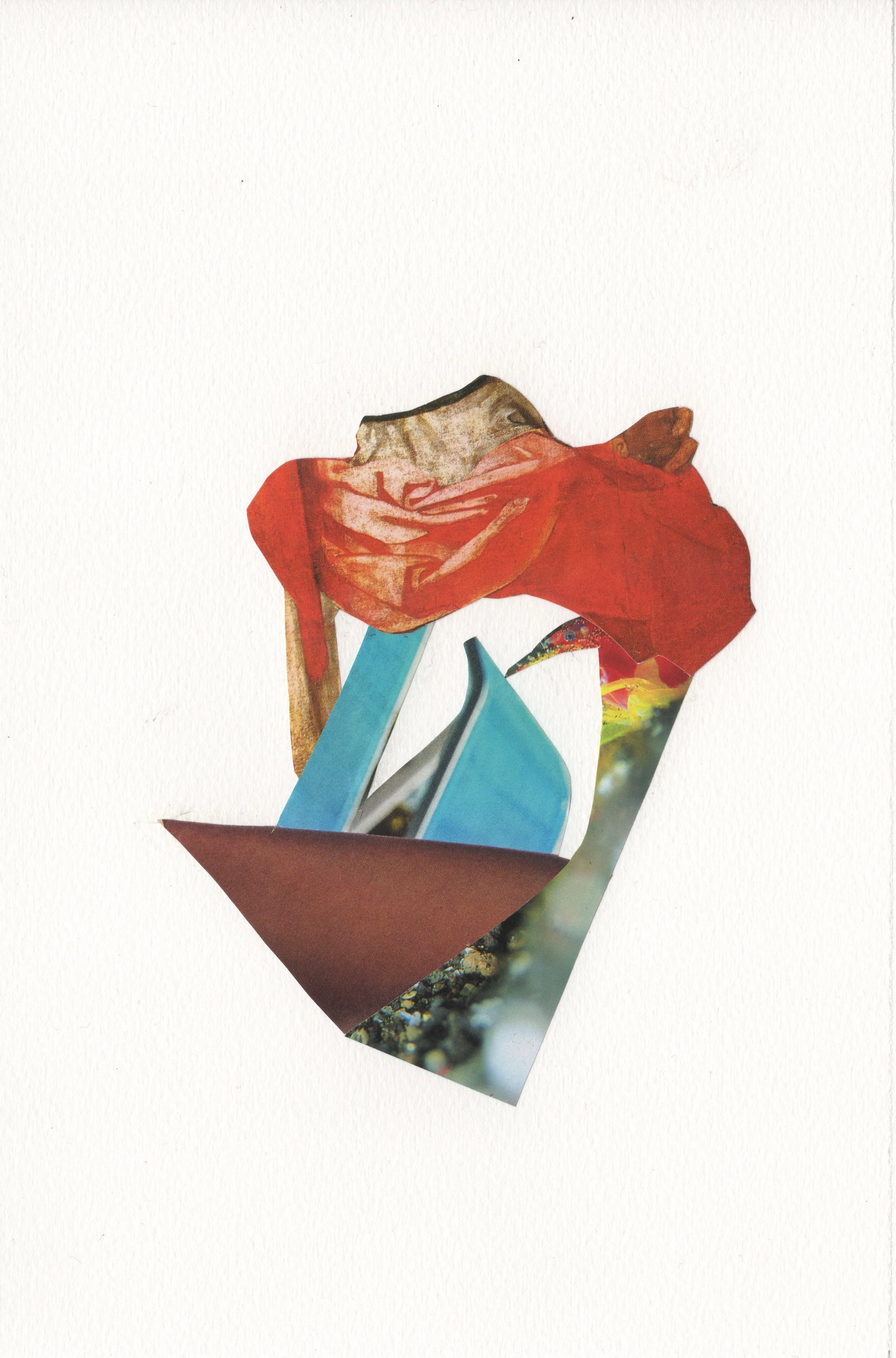

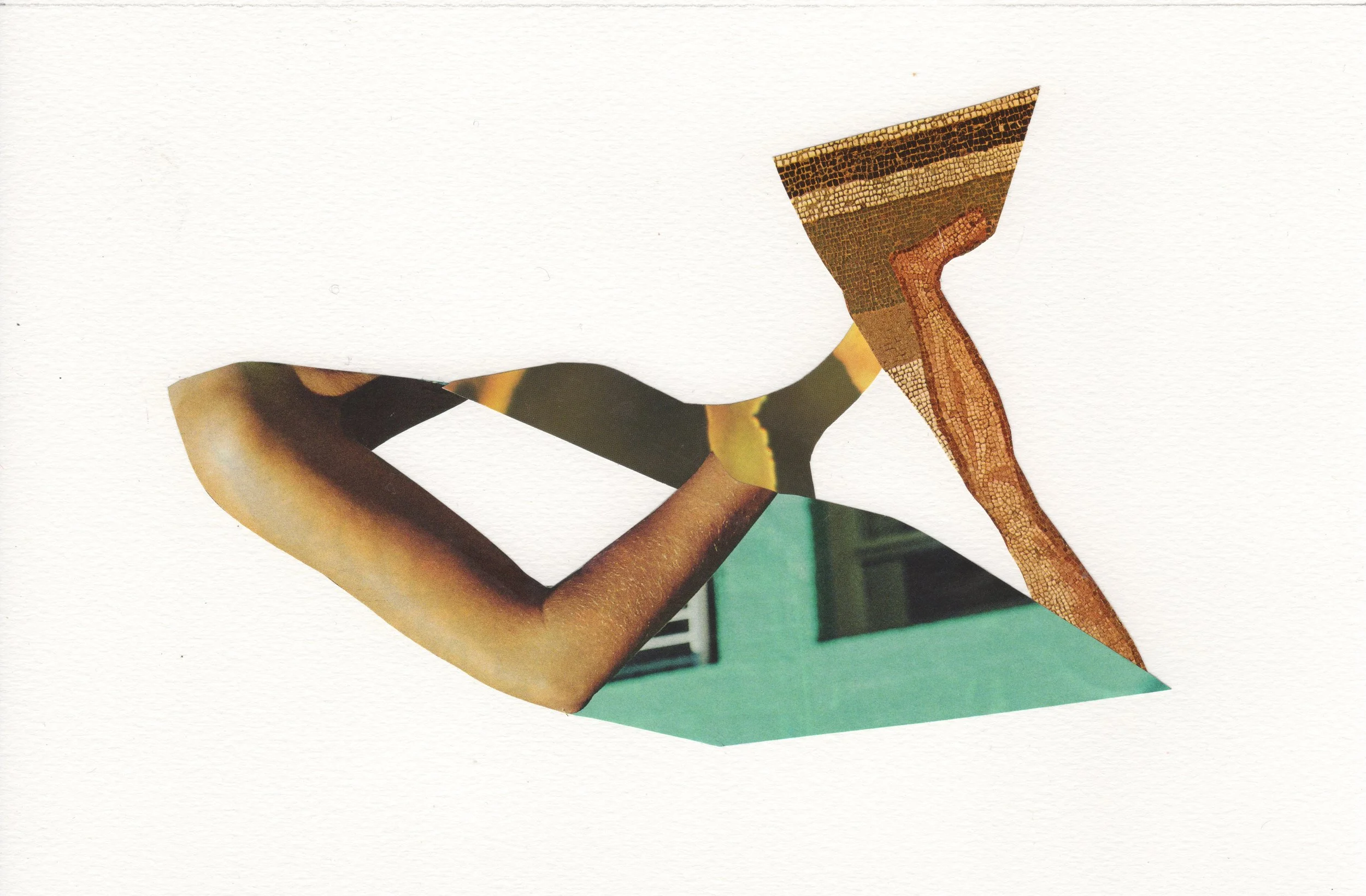

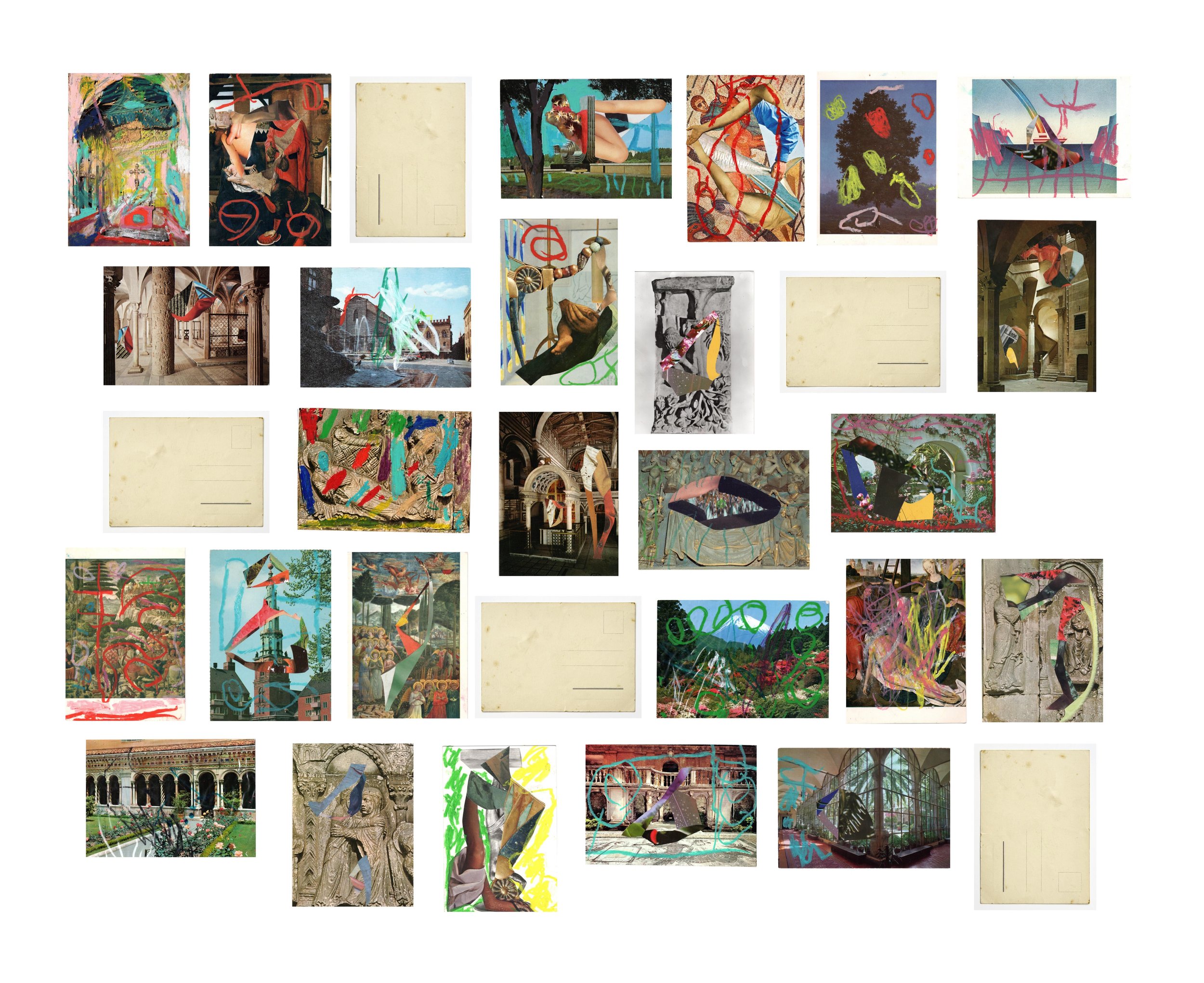

Our exhibition takes these conversations, these images, as its starting point. Guy and I and Gabrielle Mordy and Emma Johnston from Studio A continued to think and speak and make. Guy continued to draw. With Studio A, he also connected with the team at Glassworks in Canberra. There, he learnt about turning his drawings and sculptures into fragile, luminous things made from recycled bottles and the offcuts from other glass projects.

Dylan’s Morning Glory lasso on fire held our attention over the weeks and months following the workshop. What would it look like in glass? What shadows would it cast? It seemed to carry a nub, an essence of the story we were trying to visualise: forged in heat; precious but breakable…

This is just the beginning. I haven’t even mentioned the Bleeding Hearts yet! We noticed them on that first visit to the Bushlink site. Over the main road there was a patchwork of three distinct fields: one where lantana shrub had taken over, another where it was removed years ago allowing for a beautiful banksia scrub ecosystem to grow up, and a third that had been recently bulldozed. This third field was covered in small seedlings of Homalanthus Populifolios (common name Bleeding Heart), a native Australian plant that tends to come up as a pioneer species in areas that have been disturbed by human activity. A nursery plant, it provides shade for other native seeds to grow.

Like the tree emerging from Guy’s planetary atmospheric seed, this broken, sometimes burning world of ours is not beyond saving, although it’s certainly in need of tending. Thankfully, there are plenty of kind and creative Homo Sapiens to help it out.

![Will I by Colour Cage [Official Video]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b7e88f62487fd6db9bbc926/1694524984088-MXO3M5HDCPCFMPB4EFIY/image-asset.jpg)